In 2015 Prime Minister Justin Trudeau proclaimed in Paris that “Canada is back!” and committed to a 30-per-cent emissions reduction from 2005 levels by 2030.

So how is that going?

According to Canada’s most-recent submission to the UN, emissions were down a mere two per cent from 2005 levels as of 2017. If Canada was on track to meet the Paris Agreement, emissions should be down 14 per cent. Moreover, emissions in 2017 increased 1.1 per cent from 2016 levels.

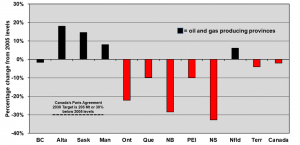

Oil and gas producing provinces were most of the problem given that oil and gas production made up 27 per cent of Canada’s 2017 emissions as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Percentage change in emissions from 2005 levels by province as of 2017.

Alberta (Canada’s largest oil and gas producer) accounted for 38 per cent of Canada’s emissions in 2017 and has increased emissions by 18 per cent from 2005 levels. In 2017 alone, emissions increased 3.3 per cent in Alberta and 11.6 per cent in the oil sands.

Saskatchewan (Canada’s second largest oil and gas producer) increased emissions by 15 per cent over the same period. Of the remaining oil and gas producing provinces, Manitoba and Newfoundland increased emissions by eight per cent and six per cent respectively and BC—with its long-standing carbon tax—reduced emissions by a mere 1.6 per cent from 2005 levels.

Meanwhile, provinces without significant oil and gas production made progress. Ontario’s emissions are 22 per cent below 2005 levels and New Brunswick and Nova Scotia are down 29 per cent and 33 per cent respectively. These reductions are largely the result of phasing out coal-fired electricity generation, but are also due to progressive policies on renewable energy and energy efficiency.

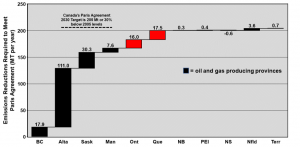

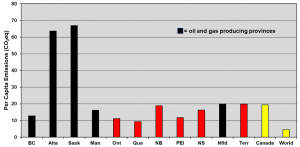

As illustrated in Figure 2, if each province were to contribute its fair share to Canada’s Paris commitment of a 30-per-cent reduction in emissions, Alberta would have to contribute more than half (54 per cent) of the remaining reduction required due to its emissions ramp up since 2005, followed by Saskatchewan (15 per cent). On a per capita basis, Alberta and Saskatchewan produced more than 60 tonnes of emissions in 2017, which is three times the Canadian average and fourteen times the world average as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 2: Annual emissions reductions required from 2017 levels if each province were to meet the 2030 Paris Agreement target (in MT per year).

Figure 3: Per capita emissions by province in 2017 compared to the Canada and World average (in yellow).

And despite 47 per cent growth in Canada’s oil and gas production, royalty payments to government have declined 59 per cent since 2000 and the proportional contribution of this sector to GDP has declined as well.

Notwithstanding the overwhelming facts to the contrary, the federal government tells us that increasing oil and gas production is necessary to meet our emission reduction targets. Prime Minister Trudeau has purchased a pipeline; Premier Horgan is providing incentives for an LNG industry in BC that will require a major ramp up of fracked gas production; and Alberta’s new premier, Jason Kenney, has vowed to increase oil and gas production.

Oil and gas are finite, non-renewable resources. The easiest to extract are gone and we are left with those requiring more extreme and environmentally damaging technologies like fracking, oil sands mining and in-situ bitumen extraction.

Having done the math and examined the scaling required for renewable technologies like solar and wind, there is little doubt in my mind that we will need oil and gas at some level for the foreseeable future to provide energy security for Canadians. But 63 per cent of current oil production is exported for marginal returns along with a large proportion of gas production. The mantra that production must increase to fund hospitals, schools and infrastructure ignores the revenue decline to Canadians who own these resources and the ramp up of emissions from producing them.

The recent election in Alberta of Jason Kenney—who vows to set up a ‘war room’ to sue groups that oppose production growth, cancel Alberta’s carbon tax, eliminate the cap on oil sands emissions and cut off oil shipments to BC—marks a new low in credible policy to meet Canada’s emissions reduction targets.

Canada needs a viable energy strategy to secure our long-term energy security and climate commitments. The facts from Canada’s latest UN emissions report and government policies doom Canada’s emissions reduction targets to fail.

This article first ran in the Calgary Herald.

Author: David Hughes

J. David Hughes is an earth scientist who has studied the energy resources of Canada and the US for more than four decades, including 32 years with the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) as a scientist and research manager.