In fewer than five years, three major dam collapses have occurred in the Americas—the most recent of which killed more than 230 people, and likely killed up to 260; many of the dead have never been recovered from the toxic mining sludge in which they were buried.

The disasters that unfolded in both British Columbia and Brazil were entirely avoidable. What needs to be done to prevent future disasters is well known. But there are troubling signs that preventive action and tougher enforcement remain elusive both in the north and the south.

The first of the three disasters occurred at Imperial Metals’ Mount Polley mine in British Columbia in August 2014. It was the worst tailings dam disaster in Canadian history, spilling 25 million cubic meters of toxic mining waste, polluting surrounding water systems, destroying salmon-spawning areas and jeopardizing livelihoods for Indigenous communities and small businesses.

The second much larger disaster happened at the Samarco mine in Mariana, Brazil in November 2015, a venture jointly owned by Vale and BHP Billiton. This dam collapse killed 19 people, destroyed homes, fields, crops and livestock, and did major damage to the entire Rio Doce river basin, which was inundated with toxic mud when the mine’s tailings dam collapsed.

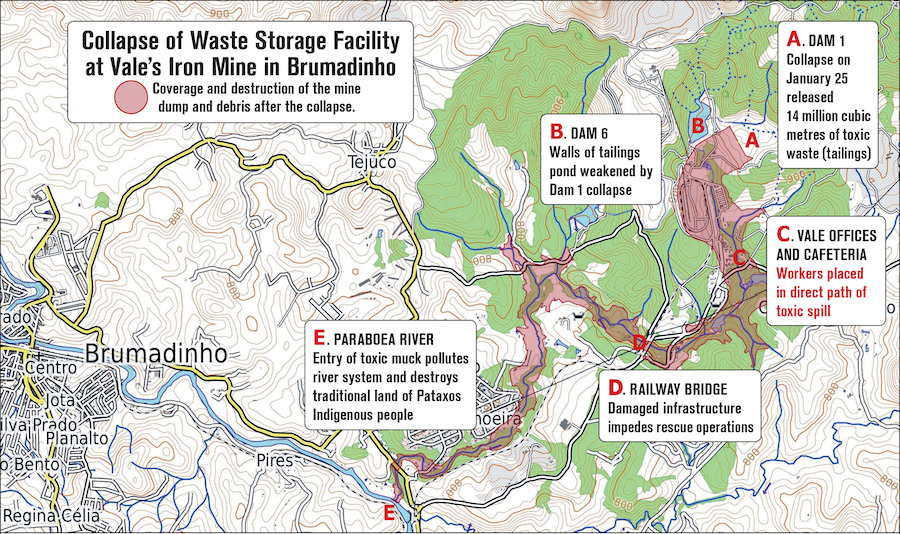

But these disasters paled in comparison to what happened this year. The dramatic collapse of another Vale tailings dam in Brumadinho, Brazil on January 25, 2019 buried mining operations, company administrative offices, cafeteria and rail lines in toxic sludge. Rescue efforts continued unabated for months afterward. By early April, the Minas Gerais Civil Defence department reported 233 dead and 37 still missing. Property and environmental damages to the Paraopeba river system are still being calculated.

What can be learned from these mining catastrophes? Can citizen anguish and indignation over what should have been preventable tragedies at Mount Polley, Mariana and Brumadinho actually translate into measures to curb the inadequately regulated power of the mining industry and reduce corporate impunity?

I raised that very question in an earlier comparative study of the tailings dam spills at Mount Polley and Mariana, subtitled “Chronicles of Disasters Foretold.” The epic scale of the tragedy at Brumadinho underscores the urgency of addressing that question before another tragedy strikes.

Let’s look at those three events.

In British Columbia

Perhaps the most troubling outcome of the Mount Polley disaster in British Columbia was the realization that such a disaster would most likely occur again barring any significant changes to the manner in which the industry was regulated.

After the disaster occurred, the BC government established an Independent Expert Engineering Investigation and Review Panel two weeks after the tailings dam collapse at the Mount Polley copper and gold mine. Norbert Morgenstern, recognized at home and internationally as an expert in geotechnical engineering, chaired the three-person panel. The panel’s final report ruled out any option for the BC government and mining industry to carry on business as usual with these much-quoted words:

“…if the inventory of active tailings dams in the province remains unchanged, and performance in the future reflects that in the past, then on average there will be two failures every 10 years and six every 30.”

The highly technical report focused on mine waste storage options and precautions. Mining technology today allows access to lower grade ores in remote ore bodies. Mining these ores becomes financially viable when commodity prices for the minerals are high. The extractive process, however, creates exponential increases in the quantities of mine waste. The mining companies operating the Mount Polley, Mariana and Brumadinho mines had all opted for wet storage facilities, constructing tailings dams that increased in height to store more and more toxic waste as mining operations continued. Wet tailings storage facilities like these need constant monitoring during the mine’s active life, at closure and, indeed, in perpetuity.

In its final report, the BC expert engineering panel recommended adoption of Best Available Practices (BAP) and Best Available Technology (BAT) for tailings dam management. The panel report explained:

“While best practices focus on the performance of the tailings dam, best available technology (BAT) concerns the tailings deposit itself. The goal of BAT for tailings management is to assure physical stability of the tailings deposit. This is achieved by preventing release of impoundment contents, independent of the integrity of any containment structures. In accomplishing this objective, BAT has three components that derive from first principles of soil mechanics:

-

- Eliminate surface water from the impoundment.

- Promote unsaturated conditions in the tailings with drainage provisions.

- Achieve dilatant conditions throughout the tailings deposit by compaction.”

The expert panel conducted a historical risk profile of tailings dams throughout BC, and recommended implementation of these approaches in phases. The panel recommended that existing tailings dams be managed using best available practices, but that at closure “BAT principles should be applied so they are progressively removed from the inventory.” The panel further recommended that BAT should be used at new tailings facilities, and that “safety attributes should be evaluated separately from economic considerations, and cost should not be the determining factor.”

Yet a study of four new and proposed transboundary copper-gold projects in the BC-Alaska border area—which was commissioned by civil society organizations in March 2016—found that not one was in compliance with the expert panel recommendations. Three of them could readily have been altered to meet these standards.1 All of these new and proposed mines will generate significantly more tailings waste than Mount Polley.

The mining industry is fully aware of the dangers of tailings storage, whether in Canada or Brazil. As the Mount Polley investigation report stated:

“Tailings dams are complex systems…also unforgiving systems in terms of the numbers of things that have to go right. Their reliability is contingent on consistently flawless execution in planning, in subsurface investigation, in analysis and design, in construction quality, in operational diligence, in monitoring, in regulatory actions, and in risk management at every level.”2

A close look at events leading up to all three collapses shows a multiplicity of things that did not “go right”—mining companies opting for cheaper over safe tailings storage methods, warnings going unheeded, whistleblowers fired, monitoring reduced, recommendation from inspections and investigations without compliance mechanisms, and a lack of adequate emergency and evacuation plans.

In my comparative study of the first two disasters, I concluded that the overarching context in both countries was one of “regulatory capture.” Mining companies had provided significant financial contributions to the electoral campaigns of the political parties in power at the time. In both countries, the elected representatives placed the interests of the mining companies ahead of the public interest.

BC’s Auditor General, Carol Bellringer, was already auditing mining enforcement and compliance when the Mount Polley disaster occurred. Her introductory comments to the Audit report made reference to the boom-bust tendencies in global commodity markets and the urgency of protecting BC’s environment, whichever market cycle prevailed.3 She argued for strong regulatory oversight from the Ministries of Energy and Mines (now the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources) and the Ministry of the Environment (now the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change Strategy). Yet Bellringer’s condemnatory report documented a decade of neglect by these Ministries in which “… almost every one of our expectations for a robust compliance and enforcement program… were not met.”4

The Auditor General tackled the core question of government capture by the mining industry. Her overarching recommendation was the creation of an integrated and independent compliance and enforcement unit to oversee the industry:

“Given that the Ministry of Energy and Mines is at risk of regulatory capture, primarily because MEM’s mandate includes a responsibility to both promote and regulate mining, our expectation is that this new unit would not reside within this ministry.”5

Bellringer’s audit also made 16 specific recommendations, some of which addressed regulatory breaches at Mount Polley.

The new provincial government elected in 2017 made some changes following that report. Contributions to political parties by corporations and unions were banned. Some efforts were also made to tighten up the practice of allowing mining industry to contract “qualified professionals” to play the regulatory roles formerly played by government regulators.6 But the central issue, the need for independent oversight of BC’s mining industry, remained outstanding. The new government also opted to stay charges in a private prosecution filed by Bev Sellars, Chief of Xat’sull First Nation at the time of the spill, along with MiningWatch and several advocacy groups. The group filed fifteen charges against Imperial Metals under the BC Mines Act and the BC Environmental Management Act.7

To date, Imperial Metals has not been fined, charged or sanctioned for the Mount Polley disaster. The toxic tailings that spilled into the pristine depths of Quesnel Lake remain at the bottom of the lake. To add insult to injury, in 2017 the BC government gave the mine company owners permission to discharge almost 60,000 cubic metres per day of tailings effluent directly into the lake. As the online investigative news site The Narwhal has detailed, “despite the terms of a permit that says this effluent must be treated, the company has been found out of compliance at least three times in 2018…[and that] despite strong penalties on paper for breaking the permit terms, the Province has to-date issued only written warnings for breaking the law.”8

In Brazil

In Brazil, the mining industry and government proceeded with business as usual after the Mariana disaster. Brumadinho was essentially a “disaster foretold.” The graffiti on many Vale properties in Brazil today says, “Brumadinho was not a tragedy. It was a crime. Vale assassinates.”

Immediately after the collapse, with hundreds still buried in muck, Vale claimed that a German consultancy company Tüv Süd had carried out recent inspections at Brumadinho and signed a deed of stability for the dam. Four days after, the Brazilian government issued 30-day arrest warrants for three Vale staff members and two Tüv Süd consultants in an effort to establish criminal responsibility.9

Nineteen days after the catastrophe, Vale CEO Fabio Schvartsman was invited to answer questions from elected deputies at a public hearing in the Federal Chambers in Brasilia. In six hours of questioning, Schvartsman maintained that Vale did not know the cause of the “accident” and that regular mine inspections had been carried out with no problems identified. At one point, Schvartsman, who had remained seated during the moment of silence to honour the victims, made this startling claim: “Vale is a Brazilian jewel that cannot be condemned for an accident that happened in its dam, however great the tragedy may have been.”10

By early March, however, Schvartsman and another senior Vale executive had “stepped down” temporarily. By this time, Brazilian prosecutors had recommended their dismissal based on evidence that the company and the auditors had colluded to present Brumadinho operations as safe even when they knew that the dam was at risk of collapse.11

In the days after the collapse, a coalition called the International Articulation of People Affected by Vale (AV) sent a three-person mission to Brumadinho. The AV report notes the confusion of roles between mining company and state after the disasters,12 a confusion not caused by the disasters but as a result of years of dismantling multiple state regulatory organizations and agencies. The report stresses Vale’s active role in disqualifying, silencing and criminalizing the organizations in Brazil that defend human rights and the environment.

The report puts in bold the three pillars of the current mining mode: it is based on legislative “flexibilization” (justified by a company narrative claiming undue state bureaucracy and delays), “self-regulation” (which allows mining companies to contract ostensibly independent professionals to attest to the security of their operations) and systematic “dismantling of the state apparatus” for compliance and enforcement. All that is missing is the Canadian innovation of Deferred Prosecution Agreements for corporate crimes. (DPAs provide another mechanism for companies like SNC-Lavalin to avoid legal prosecutions by negotiating admissions of guilt, paying fines and making promises of future good behaviour.)

Some of the AV activists are also linked to PoEMAS,13 a multi-disciplinary working group of professors and graduate students in six Brazilian universities that researches and monitors all aspects of mining in Brazil. With the credibility of both industry and government sources of information in question after a second catastrophic tailings dam collapse, PoEMAS’ publications are playing an important role. In the days immediately after January’s Brumadinho catastrophe, Folha, the main newspaper in Brazil’s largest city, São Paulo, twice ran articles on Brumadinho written by PoEMAS coordinators Bruno Milanez (construction engineer/environmentalist) and Rodrigo Santos (sociologist).

PoEMAS has now published a full report on the Brumadinho collapse entitled Minas is no longer: Evaluation of the economic and institutional aspects of the Vale disaster in the Paraopeba basin. The report stresses the increasingly central role of financialization in Vale’s corporate strategy, to the detriment of expertise and attention to the operational aspects of Vale’s mines. This includes lack of attention to the security of the company’s multiple tailings storage facilities. The report also looks at labour strategies, including reduced numbers of formally contracted, unionized employees and growing numbers of subcontracted workers amidst a generalized deterioration of working conditions including cuts in budgets allocated for health and safety.14

If we are to truly act on the lessons from Mariana, Brumadinho and Mount Polley, major changes to the global mining industry are clearly needed. Elected officials and regulators alike must ask much harder questions about whether proposed mining operations should occur at all, how much mining activity will be acceptable in a given area and under what conditions mines will be allowed to commence operations.

We also need regulatory bodies that aggressively protect the safety and health of mine workers as well as the lives and livelihoods of citizens in communities immediately affected by mining. We need to listen to and respect the rights of Indigenous people to determine industrial activity on their lands. And we need to rethink our reliance on mining in light of the growing ecological and safety risks the industry poses.

In short, we need to heed the warning signs that other disasters are imminent and do what we can now to minimize those risks.

Notes

1. Mining Watch. (2016). Post-Mount Polley tailings dam safety in transboundary British Columbia.

2. Independent Expert Engineering Investigation and Review Panel. (2015). Report on Mount Polley tailings storage facility breach, 119. Victoria: Province of British Columbia.

3. Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia. (2016). An Audit of Compliance and Enforcement of the Mining Sector, 3.

4. Ibid., 3.

5. Ibid., 11.

6. Smith, S. (2018, June 29). Professional reliance reform is a step forward for BC: BCGEU. BC Government and Service Employees’ Union.

7. Hoekstra, Gordon. (2018, January 30). B.C. government stays charges in Mount Polley private prosecution. Vancouver Sun.

8. Pollon, Christopher. (2018, October 24). Year four: Tracing Mount Polley’s toxic legacy. The Narwhal.

9. Phillips, Dom. (2019, January 29). Brazil dam collapse: Five arrested including three mining firm staff. The Guardian.

10. RT en Español. (2019, February 15). Presidente de la minera Vale dice que la firma “no puede ser condenada” por la tragedia que dejó 166 muertos en Brasil. RT en Español.

11. The Economist. (2019, March 9). Beyond the Vale: Vale and the aftermath of a devastating dam failure. The Economist.

12. International Articulation of People Affected by Vale. (2019, February 25). Nota um mês do crime-tragédia de Brumadinho (Author’s translation). International Articulation of People Affected by Vale.

13. Poemas means poems. As an acronym, it stands for Grupo de Pesquisa e Extensão Política, Economia, Mineração, Ambiente e Sociedade (Politics, Economy, Mining, Environment and Society). The titles of PoEMAS’ studies are all taken from poems by Brazil’s much loved poet, Carlos Drummond de Andrade, who lived in a mining area and wrote often about mining.

14. The full report, Minas não há mais: avaliação dos aspectos econômicos e institucionais do desastre da Vale na bacia do rio Paraopeba, is available in Portuguese. The executive summary, Minas is no more, is available in English.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of Canadian Dimension.

Author: Judith Marshall

Judith Marshall is a Canadian popular educator and writer. She worked for eight years in the Ministry of Education in post-independence Mozambique, designing curricula for workplace literacy campaigns. On her return to Canada, she completed a PhD at the University of Toronto with a thesis—and later book—on literacy, power and democracy. She has recently retired after two decades in the Global Affairs department of the United Steelworkers, which included member education on global issues and the organization of many international exchanges of workers, especially in the mining sector. She is now an Associate of the Centre for Research on Latin America and the Caribbean at York University in Toronto.