September 30, 2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the opening of the first large oil sands mine and processing plant in Fort McMurray. The facility was developed by Great Canadian Oil Sands, the precursor to Suncor Energy, which is one of Canada’s largest producers of fossil fuels.

Over the past five decades, the northern Alberta oil sands deposits have gone from a relatively unknown source of heavy oil to a core part of North America’s energy economy.

Here are five things that Albertans and Canadians should consider as we mark the 50th anniversary of large-scale oil sands extraction, and contemplate what it means to recognize Indigenous title and rights as Alberta transitions to a different kind of economy.

1. The development of the oil sands was made possible by huge government investments and low royalty and corporate tax rates

Gillian Steward’s June 2017 Parkland Institute report explains that after operations began in 1967, the oil sands industry was expanded in the 1970s through massive investments by the provincial government in the Alberta Energy Company (AEC) and the Alberta Oil Sands Technology and Research Authority (AOSTRA).

Premier Peter Lougheed, who was Alberta’s premier from 1971 until 1985, established the AEC in 1973. The province owned 49% of the corporation and the remaining equity came from individual Albertans. The AEC became the vehicle for Lougheed to promote oil sands development, particularly Syncrude.

Lougheed established AOSTRA the next year. AOSTRA was a government-funded agency, and one of the largest research and development programs ever launched in Canada. AOSTRA played a critical role in developing steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) and in situ extraction technologies, which are the future of oil sands extraction.

As Steward explains in Betting on Bitumen:

In 1975 the proposed Syncrude project was near collapse after partner company Atlantic Richfield withdrew its support. Alberta, Ontario, and Ottawa had been counting on this new megaproject to provide jobs and secure Canada’s oil supply and were keen to see it succeed, as was the Syncrude consortium. In a series of negotiations the remaining partners in the project—Imperial Oil, Cities Service, and Gulf Oil (which took over Royalite in 1969)—used Atlantic Richfield’s withdrawal to force both levels of government into granting unprecedented concessions. In the end Alberta, Ontario, and Ottawa all became partners in the project, with Alberta doing so through the Alberta Energy Company. Alberta also paid infrastructure costs, including a $300 million utility plant and a $100 million pipeline from Fort McMurray to Edmonton. The province also built community schools, bridges, highways, and other services. Syncrude received the world price for its oil when the [Canadian] oil industry in general was receiving a much-lower Canadian price, and its private corporate partners received generous write-offs not only on expenses directly related to the oil sands plants but also on exploration and development projects in other parts of their operations.

Unlike Lougheed, who saw government as a counterweight to the economic power and influence of the oil industry, Ralph Klein, who was Alberta’s premier from 1992 through 2006, thought government should step aside, and his government gave almost full rein to the industry while sidelining other stakeholders.

Klein’s strategy was almost entirely developed by the Alberta Chamber of Resources (ACR), an industry association which launched the National Task Force on Oil Sands Strategies in 1992. The industry-dominated task force released a report in May 1995, offering 23 policy recommendations for the provincial and federal governments, including recommended tax and royalty changes and environmental regulatory reform. Just six months after the release of the report, Klein announced that the province’s new royalty regime, essentially written by the industry-dominated task force, would apply to all new oil projects in Alberta.

The royalty regime brought us both the penny-on-the-dollar pre-payout royalty and the Accelerated Capital Cost Allowance for Oil Sands deal. The claim is made that the oil sands wouldn’t have taken off were it not for those initiatives, but they remained in place even during the boom when corporate profits were skyrocketing and there was no longer a need to incent investment.

At the same time that the Klein government introduced the new royalty regime, it cut staff that handled oil project approvals and streamlined the process. The new process introduced self-regulation, which meant oil sands corporations became responsible for regulating themselves.

In the 1996 federal budget, the government of Canada also made the corporate tax changes the industry-dominated task force had recommended 10 months earlier.

In 2000, premier Klein cut Alberta’s tax rate for large corporations from 15.5% to 10%, reducing the provincial government’s revenue by an estimated $30 billion from 2001 through 2014, a period when Canadian and international oil companies made record profits.

Earlier this year, Parkland Institute released results from a public opinion poll showing that 61% of Albertans think large corporations do not pay enough in taxes.

2. During the boom years, the oil sands were responsible for less employment than some claimed, and many of the jobs lost after the 2014 downturn may not come back

As Eric Pineault and I wrote in an April 2017 blog on oil industry restructuring, “even during the boom years, the oil sands were not responsible for as much employment as some claimed. In 2006, at the height of the boom, the mining and oil and gas extraction industry accounted for just 6.7% of Alberta’s total employment.”

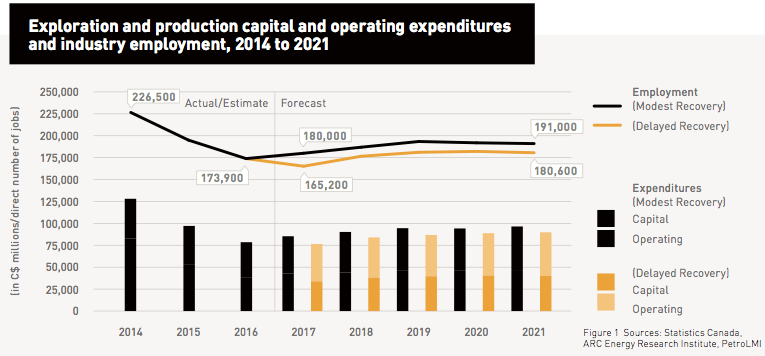

The oil price downturn that began in mid-2014 saw significant industry restructuring and the (perhaps permanent) elimination of over 30,000 jobs. A recent five-year labour market forecast for Canada’s oil and gas industry says by the end of 2021 the industry will at best recover one-third of the 52,600 jobs lost between 2014 and 2016 as a result of the downturn. This “modest recovery” case (see black areas in the chart below) assumes US$55 per barrel in 2017, increasing to US$75 by 2020-2021—a fairly optimistic scenario.

The “delayed recovery” scenario (in orange in the above graph) assumes job losses will slow somewhat but continue in 2017. In this case, the industry is projected to lose a total of 61,300 jobs between 2014 and the end of 2017, but recover only 15,400 jobs between 2018 and 2021 (or about one in four lost jobs). This scenario assumes US$46.50 per barrel in 2017, increasing to US$60 by 2020-2021.

If the modest recovery prediction comes true, then the projected 191,000 industry jobs in 2021 would account for 8.4% of Alberta’s total employment in August 2017.

The Petro Labour Market Information report seems to point to the fact that despite what many believe or are hoping for, Alberta isn’t on the cusp of an oil industry recovery, but that we are in fact in the midst of a major oil industry restructuring and longer-term low price environment here in Alberta and globally.

3. The recent “Canadianization” of oil sands ownership further enmeshes the industry with Canadian banks and the savings of Canadians

The oil price downturn that began in mid-2014 has forced oil corporations of all sizes, both here in Canada and globally, to review their strategies. As Eric Pineault and I wrote in April, “the status and value of oil sands assets—both extractive facilities and reserves—are being revised in the process.”

The last three years has seen international oil majors like Shell, ConocoPhillips, Statoil, and others exit the Alberta oil sands, and Canadian oil majors Canadian Natural Resources Limited, Suncor Energy, and Cenovus Energy double down on their oil sands investments.

What does this Canadianization of oil sands ownership mean? Beyond the significant and negative labour market implications discussed above, Canadians should be concerned about their savings, particularly their pension funds and mutual funds, being tied to an industry characterized by boom-and-bust cycles, especially in light of the Paris Agreement and the likelihood that more stringent global agreements to mitigate global warming will be passed in the future.

4. The oil sands are Canada’s fastest growing source of greenhouse gas emissions, and Alberta’s emissions cap allows emissions from oil sands production to grow another 47%

Several of the oil sands majors are in favour of the government of Alberta’s emissions cap—not surprisingly given Prime Minister Justin Trudeau pointed to the cap as part of his government’s rationale for approving two new oil sands pipelines in November 2016 (before Bill 25, the Oil Sands Emissions Limit Act, had even received royal assent).

The cap allows emissions from oil sands production (i.e. from extraction and processing) to increase 47% above 2014 levels. If Enbridge’s Line 3 and Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Expansion Project pipelines are eventually built, then the emissions cap will have helped enable a massive increase in emissions from Alberta oil burned outside of the province’s borders.

Canada’s role as a major exporter of fossil fuels and greenhouse gas emissions—chiefly through the emissions embedded in Alberta’s oil—is why Prime Minister Trudeau and Premier Notley fit to a T the definition of the new climate denialism. Trudeau and Notley claim to be climate leaders, yet their policies and pipeline approvals tell a different story.

5. The oil sands exist largely on Indigenous lands, yet it is mostly non-Indigenous people who have approved of or benefited from oil sands developments

The concerns of Indigenous people are still mostly not taken seriously by oil corporations and the provincial and federal governments.

In the two years since the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) report, there has been inadequate action by provincial and federal governments to implement the TRC recommendations.

In an interview with CBC television last week, Pam Palmater, Chair of Indigenous Governance at Ryerson University, lambasted Prime Minister Trudeau for the framing and content of his speech on reconciliation at the United Nations.

In Alberta, Premier Notley wrote a letter to her cabinet ministers shortly after the 2015 provincial election victory, in which she said her government would “[consider] the objectives of the UN Declaration [on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples].” The premier’s letter also stated:

… our government is committed to renewing and improving our relationship with Indigenous peoples. We intend to work with Indigenous peoples as true partners to ensure that:

– Their constitutional rights are protected;

– The air, land and water that they, and all our communities, rely on is protected; and

– They can build more prosperous, self-reliant and culturally strong communities.

The Alberta government has made some movement on implementing the mandate expressed in the premier’s letter. In February, for example, the province signed a 10-year framework agreement with the Métis Nation of Alberta, emphasizing a relationship based on recognition, respect, and cooperation. In March, Alberta and the Blackfoot Confederacy signed a protocol agreement on how they will work together on economic development and other areas of concern to both parties.

The Notley government deserves credit for engaging in these new partnerships, but Alberta and Canada have a lot more work to do if “reconciliation” is to be more than a buzzword.

In March, my Corporate Mapping Project colleague and Bigstone Cree Nation (BCN) member Angele Alook wrote a letter of concern because “CNRL and Husky Energy plan to remove a combined 760 truckloads of water [from BCN territory] every day for 20 years. CNRL alone has stated the draw-down effect to surface water is an estimated 3–8 metres, meaning there will be no South Wabasca Lake in 20 years; it will be nothing more than a shallow creek not fit to drink from.”

In June, Angele Alook, Nicole Hill, and I wrote that the “detrimental health effects of oil sands development for Indigenous people is not a new topic in Alberta political discussions.” We noted that Chief Allan Adam of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation expressed disappointment in January that the Alberta government is still approving new projects and that his “people are still being diagnosed with cancer at an alarming rate … [Neither] the federal [nor] the provincial government has done anything [in] regards to a health study that we keep lobbying for. Nor does industry want this health study to commence.”

A lot has changed since Alberta’s first oil sands mine started producing bitumen 50 years ago. Once seen as the key to long lasting prosperity in Alberta, the oil sands are no longer such a sure bet, and the industry and province are at a crossroads.

Amid uncertainty about the economic viability of the resource in the years ahead, increasing global recognition that we must begin to contemplate a future without fossil fuel extraction, and important questions about what it means to truly recognize the rights and title of Indigenous peoples, we in Alberta and Canada must decide which path to take in the next 50 years.

We can continue to implement policies in Ottawa and Alberta that meet the approval of the oligopolistic bloc of eight corporations that produce and transport most of Alberta’s oil. This path will mean we miss our Paris Climate Agreement obligations and, over the next five decades, will strengthen Alberta’s and Canada’s ties to oil and gas production during a period in which other countries are undergoing a deep transition away from hydrocarbons.

Or, we as Albertans and Canadians can choose a path of transitioning to a different kind of economy. We can make a just transition by developing policies that recognize and respect Indigenous rights and title, that put thousands of people to work cleaning up land that’s been polluted by Alberta’s oil industry, and that minimize the impacts of such a transition on oil and gas workers by involving them in building our new economy.

Alberta is in transition and we must start seriously planning for a different kind of economy.

This blog is part of the Corporate Mapping Project, a research and public engagement initiative investigating the power of the fossil fuel industry in Western Canada. The CMP is jointly led by the University of Victoria, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, and Parkland Institute. This research was supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Author: Ian Hussey

Ian Hussey is a research manager at Parkland Institute. He is also a steering committee member and the Alberta research manager for the SSHRCC-funded Corporate Mapping Project. Before joining Parkland Institute, Ian worked for several international development organizations, including as the co-founder and executive director of the Canadian Fair Trade Network. Ian holds BA Honours degrees in Sociology and in English from Acadia University, an MA in Sociology from the University of Victoria, and his PhD courses and exams at York University focused on the sociology of colonialism and on political economy. His writing has appeared in the Globe and Mail, New Political Economy, Edmonton Journal, National Observer, and The Tyee.