In 2006 Statistics Canada drew attention to a troubling relationship between women’s equality in Alberta and the growth of extractive industries in the province. The report noted that while women in Eastern Canada were reaping the rewards of increasing education levels, greater access to affordable childcare, lower birth rates, and greater income equality, all these same indicators were heading in the opposite direction for women in the West. The study showed that expansion of Alberta’s primary resource industry had boosted employment opportunities for men, but had left women seeking out part-time employment despite the labour market’s growing demand for full-time workers.

What the report addressed was the almost mundane point that oil economies gender the labour market to men’s benefit. But despite years of numbers backing up this claim, consecutive provincial and federal governments have remained largely indifferent to the extractive industry’s impact on women’s equality in the province.

Over the past two decades, the growth of Alberta’s extractive industry has created a second-order labour market that has consistently positioned the province in the bottom tier for gender equality. In fact, in 2016, 10 years after the release of Statistics Canada’s report, the United Nations Human Rights Committee released its sixth periodic report of Canada, in which it stated its concern about persisting inequalities between men and women, and singled out Alberta for its high pay gap, which the report noted was disproportionately impacting Indigenous and racial minority women.

In a 2015 report released by Parkland Institute, Kathleen Lahey cautioned that unless the direction of Alberta’s economic development changed soon, and with special attention paid to women’s economic rights, then the negative effects of oil’s inevitable booms and busts would result in far more economic damage to women than men.

Now, two years later—with the province entering year three with an NDP government at the helm, a new budget having just been released, and a creeping growth in oil prices being cautiously observed—it seems an opportune time to evaluate the state of Alberta’s gender equality. How are Alberta women faring in comparison to women across the country? How has their economic and social status been influenced by the resource sector? And finally, has Alberta moved any closer to narrowing the gender pay gap and redirecting the province’s course of economic development toward a more environmentally sustainable path?

Resource extraction and Alberta’s gender pay gap

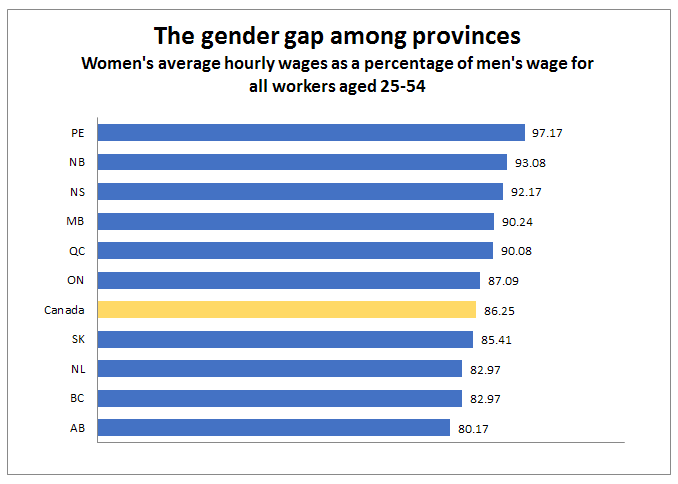

A recent gender equality scorecard released by Oxfam Canada to mark International Women’s Day ranks Alberta last in Canada, with the province having the widest gender pay gap in the country. In turning to Statistics Canada data of women’s average hourly wages as a percentage of men’s aged 25-54, the report found that women in the province only earn 80.17 cents an hour for every dollar men earn, well below the national average of 86.25 and even further below the country’s Atlantic provinces, where women earn a minimum of 92% the hourly wage of their male counterparts. In a 2016 Parkland Institute report, Kathleen Lahey found that even when measured in terms of women’s full-time, full-year earnings, women in Alberta were still making on average $31,100 less than their male colleagues. Across the board, Indigenous and racial minority women also fare far worse than their white counterparts.

Source: The Globe and Mail

In Alberta, identifying one of the primary culprits behind the persistent gender pay gap isn’t difficult. Occupational segregation is a primary contributor to the gender wage gap, and the province is well-known for its economic reliance on the male-dominated oil and gas sector. Taking a closer look at regional differences in the pay gap makes this industry’s influence even more clear.

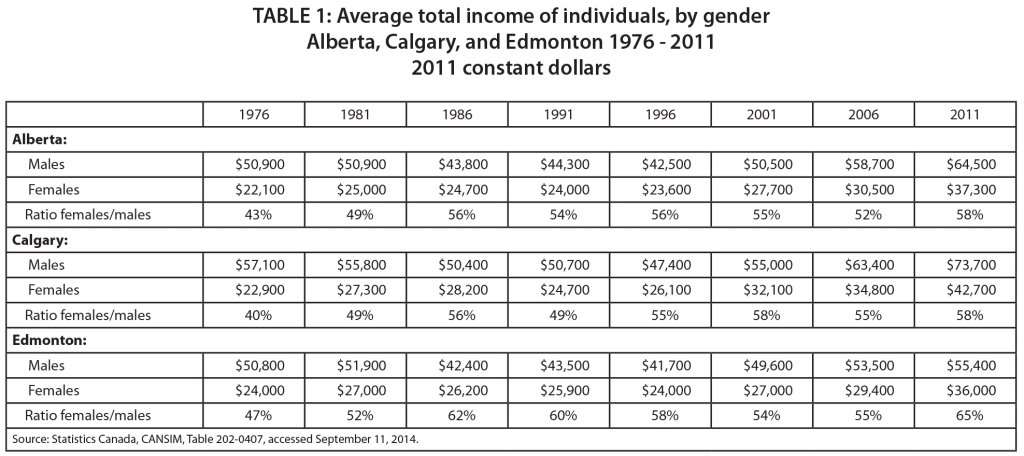

In her 2015 report, Lahey found that both absolute income levels by gender and gendered income ratios varied significantly between Calgary and Edmonton. In 1976, women’s incomes in Edmonton started out at 47% of men’s, and by 2011 had risen to 65% of men’s. In contrast, during the same period, women’s incomes in Calgary started out at 40% of men’s, and by 2011 had only risen to 58% of men’s.

Again, referring to Lahey’s report, if we look at the numbers only for those employed in full-time, full-year work, the gender pay gaps are even bigger. In 2011, average men’s earnings in Edmonton were $25,000 higher than women’s, and in Calgary men’s earnings were nearly $35,000 higher than women’s.

These regional differences reflect the extractive industry’s favoritism towards men. As Lahey notes, “resource extraction industries hire far more men than women, and employ large numbers of highly paid executives, managers, technical employees, and skilled labourers—all occupations in which women are markedly under-represented.”

Private vs. public employment

While perhaps tempting to ask ourselves (as industry has) how we can get more women into hardhats, the answer to closing Alberta’s gender wage gap isn’t to increase female representation in the oil and gas sector, but rather to diversify our economy and gradually phase out our reliance altogether. The main reason for this is that among occupations, the natural resources sector has the largest gender disparity in the country, meaning that regardless of increased female representation, women would still fare poorly in the province. The Oxfam report finds that in Canada’s natural resources sector women’s hourly wages are only 70.09% of men’s. In contrast, women employed in health care make, on average, 94.49% of men’s wages.

This discrepancy illustrates another important point: differences in the gender pay gap between the public and private sector are substantial, and further speak to why gendering the oil industry’s workforce is unlikely to improve women’s economic status. In a 2014 report published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Kate McInturff and Paul Tulloch found that women across the country are hired at lower starting salaries and experience stunted rates of promotion—what they described as, “a sticky floor to go with the glass ceiling.” This finding was particularly pronounced for the private sector, where women were paid 20% less than their male counterparts.

Public sector pay scales make a significant contribution to narrowing the gender wage gap—not by paying everyone more, but rather by paying women and men more equally. Taking age and education levels into account, women across the board in every age group, with and without post-secondary education, face less wage discrimination in the public sector than they do in the private. Across the board, McInturff and Tulloch found that women were paid 22% less than men in the public sector and 27% less than men in the private sector. And while this extra 5% may not seem like much, they highlight that it amounts to $2,689 a year, or roughly a month’s worth of a family’s basic necessities. However, compromising these more equal employment opportunities is the province’s oil-funded approach to social programs.

Resource revenue and Alberta’s boom-and-bust budgets

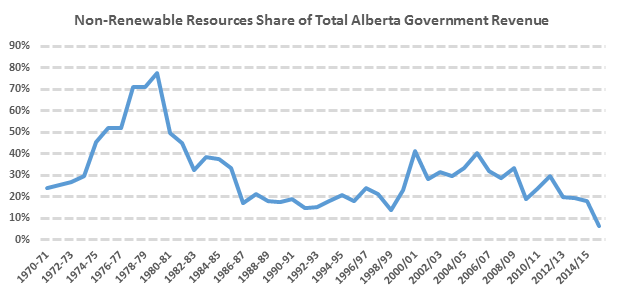

Alberta’s stubborn budgetary reliance on resource revenues has prevented the province from developing a reasonable fiscal system, which has left its public sector particularly vulnerable to oil price fluctuations. Instead of building its revenue system on broad-based flows of income, Alberta has used resource royalties and other oil and gas receipts to fund significant portions of the provincial budget. As Lahey points out, since 1970, resource revenues have accounted for as much as 77% of Alberta’s budget (in 1979), and at least 14% (in 1999). However, Alberta’s 2015-16 budget recorded the lowest on record, with non-renewable resources making up a mere 5.7% of the province’s total revenue for the year.

Source: Trevor Tombe, October 27, 2015, Maclean’s Magazine

This consistent reliance on oil and gas revenues has resulted in extreme fluctuations in public spending that follow the cyclical pattern of oil prices. During boom periods, royalty revenues have allowed the government to effortlessly expand the welfare state without resorting to income taxes. This has left Albertans expecting programs to be there without having to be paid for out-of-pocket. Yet, during the inevitable busts, consecutive conservative governments have responded by mimicking the business tactics of the oil and gas sector by dramatically cutting program spending and decreasing or postponing capital spending.

As one might expect, this boom-bust cycle of public spending is far from gender neutral. Rather, women are particularly hard hit, both because they are employed by these sectors, and because they disproportionately rely upon the services they provide. The Alberta government is a leading employer of women in the province; according to Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey, in 2014 women accounted for 82% of those employed in healthcare and social assistance, amounting to a total of 197,300 workers, or 19.4% of all employed women in the province. The public sector acts as a significant provider of economic security for women because of its smaller gender pay gap. Women’s economic security in the province is always at risk when public spending is so closely tied to unpredictable resource revenue.

Assessing gender progress in the province

The May 5, 2015 election of an NDP government resulted in Alberta being stripped of its troubling status as the only Canadian province without a minister responsible for the status of women. After campaigning on a commitment to address equity issues, the Notley government appointed the first cabinet to achieve gender parity in Canadian history, promising to usher in a new era of inclusive governance.

The government has since delivered on a number of its campaign commitments: it has made its $15 minimum wage official and has adjusted the province’s flat tax regime, adding new brackets for high-income earners that place additional revenue in government coffers. Women in the province have also benefited from the ongoing post-secondary tuition freeze, and lower-income families (including single parents) are now better supported due to the introduction of the Alberta Child Benefit and enhancement of the Alberta Family Employment Tax Credit. The Status of Women Ministry has also shown an earnest commitment to preventing and addressing gender-based violence in the province. In 2015, it increased guaranteed annual funding for women’s shelters, including for on-reserve shelters which, being funded federally, hadn’t seen funding increases since 2007.

In its 2016 budget, the government also allocated $7.55 million to the Ministry for the Status of Women, earmarking $2.28 million for gender equality and advancement and another $2.9 million for gender policy, strategy, and innovation. As reported by Parkland last year, the latter’s mandate includes adopting gender-based analysis for 25%, 50%, and 75% of government policies and programs in 2016, 2017, and 2018, respectively.

Now with the introduction of its third budget, referred to by the government as the “Working to Make Life Better” budget, the obvious question is, better for whom? Is the NDP on the right track to re-routing the province’s course of economic development? Is their commitment to “gender mainstreaming” and women’s equality reflected in their fiscal plan? Are they—as promised—finally a government looking out for the economic and social well-being of Alberta women?

With oil prices recovering slightly, the government is still confronted by its usual bitumen-based predicament. Non-renewable resource revenue is budgeted at $3.8 billion in 2017-18, well below averages seen over the past decade. However, as noted by a previous Parkland blog, the province’s spending levels, deficit, and debt hardly indicate a provincial state of emergency. In fact, the government’s most immediate challenge is to collect enough revenue to maintain the social programs upon which progress towards women’s equality depends.

Likely due to this revenue shortfall, the government has trimmed the Status of Women’s budget from $7.55 million in 2015-16 to $7.4 million in 2017-18. The government has reiterated its commitments to ending violence against women and girls, increasing women’s economic security, and boosting women’s representation in leadership roles across the province.

Yet, alongside the budget’s promise to advance women’s equality is the glaring expectation that non-renewable resource revenue will soon bounce back to carry the government’s fiscal plan for the next three years. As Todd Coyne put it in a recent CBC article, “As Alberta budgets always do, this one begins and ends with the oil price.”

The government is banking on a US benchmark oil price of $55 over the next year, and rising to $68 by 2020. It is also expecting a decline in conventional crude assets, relying instead on the prediction that bitumen production will increase by more than 400,000 barrels per day over the next year. Despite the assertion that “diversifying the Alberta economy and lowering dependence on energy prices is considered a prudent solution to the energy roller coaster Alberta is on,” the budget indicates that the government is far from breaking with tradition, relying on the tar sands to bankroll a significant chunk of public spending over the next three years.

The government’s incremental royalties structure will see more operations paying higher royalty rates as production costs fall and revenues rebound. This is expected to increase the government’s royalty revenues from $2.5 billion over the next 12 months, to $3.2 billion in 2018-19, before hitting an estimated $5.2 billion in 2019-2020.

The government seems hardly committed to redirecting the province’s course of economic development. At a time when the government should be curtailing its dependence on resource revenues, it’s instead choosing to bet on their rebound. In 2017-18, the government is counting on non-renewable resource revenues accounting for 8.3% of total revenue, with its share expected to grow to 12.8% of revenue by 2019-20.

This ongoing dependence on non-renewable resource revenues is not only strengthening the ties between the public sector and oil price volatility, but is also further distancing the province from its stated goal of achieving economic equality for Alberta women. As history has shown, women are disproportionately impacted by Alberta’s resource-dependent economy. By doubling-down on resource revenues and failing to diversify its revenue streams, the province will—to the embarrassment of all Albertans—continue to rank last in Canada when it comes to gender equality.

Author: Emma Jackson & Ian Hussey

Emma Jackson is a settler on Treaty 6 land, where she recently completed her MA in sociology at the University of Alberta. Her research interests include feminist political economy, transnational migration, and geographies of resource extraction. Emma has a degree in geography from Mount Allison University, and over four years experience as a student organizer with the Canadian fossil fuel divestment movement. She was a research assistant at Parkland Institute for the SSHRC-funded Corporate Mapping Project from September 2016 through December 2018.

Ian Hussey is a research manager at Parkland Institute. He is also a steering committee member and the Alberta research manager for the SSHRCC-funded Corporate Mapping Project. Before joining Parkland Institute, Ian worked for several international development organizations, including as the co-founder and executive director of the Canadian Fair Trade Network. Ian holds BA Honours degrees in Sociology and in English from Acadia University, an MA in Sociology from the University of Victoria, and his PhD courses and exams at York University focused on the sociology of colonialism and on political economy. His writing has appeared in the Globe and Mail, New Political Economy, Edmonton Journal, National Observer, and The Tyee.