The province of Alberta, specifically its northern oil sands region, is often described as a frontier—a harsh landscape, rich with potential for those “tough” enough, “strong”enough, and “man” enough to make it. Unfortunately, like the frontiers of old, the mythologized frontier of present-day Alberta is rife with inequality, marginalization, and oppression for those who do not fit the traditional ideal of a strong (white) man.

The March 2nd speech from the throne speaks from this frontier mentality. For example, the speech describes Albertans as “everyone who made the decision to call this northern slice of the continent their home and never looked back.” The speech refers to Alberta’s values (including “hard work”) as a “North Star,” and explains the importance of all Albertans as “one people on a common journey towards a common future.”

The speech ends with a reference to Albertans’ fabled toughness: “Grit built this province. Grit will build its future. As a province, we have had our ups and downs. Though the world around us may be growing more uncertain, your government will remain calm and focused. Now is not the time to let our steady hand waver.” The background imagery throughout is reminiscent of historical tales of wagon-trains of settlers working together to survive harsh conditions and uncertainty.

This frontier theme sells Albertans not as a mostly urban, well-educated population, but as individuals who must work together to keep the good ship Alberta afloat as we ford unforgiving rapids to reach a better future. Although many Albertans may identify with this sentiment, it is important to consider the less romantic details about frontiers of the past, and the people who were—and continue—to be marginalized.

Albertans are living in a corporate-dominated province overly focused on the oil and gas sector, in a settler-colonial country that is built on an intersectional hierarchy of value that sees heterosexual, white, male workers benefit because of the super-exploitation of gendered and racialized people (as well as other intersections of marginalization not focused on here). That is, in a corporate-capitalist economy, like present-day Alberta, even high-wage workers are exploited, otherwise employers would have no interest in hiring them (more on this below), but gendered and racialized people tend to be confined to precarious, marginal positions in which their low wages contribute to especially high profits, some of which can be diverted to cover the higher wages of white male workers.

Alberta oil and the frontier mentality

Categorizing a place such as Alberta as “a frontier” is a colonial concept. When we think of Alberta as a frontier, we overlook the reality that Indigenous peoples lived on this land for a very long time prior to the arrival of settlers, having their own complex relationship with the land to successfully maintain a subsistence-based lifestyle.

Social scientists O’Shaughnessy and Dogü describe masculinity in Alberta’s northern resource industries as “frontier masculinity,” that which is “strong, rugged, self-sufficient—conquering the dangerous wilderness in the hope of striking it rich” (p. 268). Frontier masculinity defines masculinity against “all that is deemed incapable of enduring the tough conditions of the frontier”; that is, the feminine, urban, and non-white (p. 268). Women in this context are defined by their relationships to men and their ability to support men and their work.

In the context of the frontier, being self-sufficient through employment is of the utmost importance—having a “good job” matters.

‘Good jobs’ in Alberta’s oil industry and their effects on family health

Another theme of the 2017 throne speech is that of “good jobs”; the phrase appears nine times in the speech. For example, the speech states, “Alberta’s energy industry creates good jobs, and good jobs are the bedrock of a strong province.”

The speech prompts two questions: What is a “good job”? And, who has access to “good jobs” in Alberta’s oil industry?

Let’s start by defining a “good job.”

Beyond producing a decent income, labour researcher Andrew Jackson finds that job security, physical conditions of work, work pace and stress, working time, opportunities for self-expression and individual development at work, participation at work, and work-life balance also factor into a job’s “goodness.”

Most jobs directly in the resource extraction industry involve working very long shifts (often 12 or more hours a day), and days and sometimes weeks away from home and family at work camps. These may be considered good jobs for those who are able to earn a high income during the winter months when the ground is frozen, and then have the option to take summer months off.

A common theme in Alberta seems to be those who say, “I came to Alberta for a short time, made a lot of money, and then went back home.” This seasonal cycle of working away and then coming home may be manageable for some individuals. However, working long shifts and spending weeks away from home at work camps puts extra strain on families and communities, not only because of the time apart but also because those left at home (often women) end up doing most of the cleaning and caring work.

There are some oilfield maintenance jobs, where labourers may work at the same plant or refinery without having to migrate for work. However, the nature of resource extraction means there are always new areas of exploration or major projects leading the industry to rely on a more migratory workforce.

One of the authors of this blog lived this type of seasonal schedule for years, in which her partner worked in the trades and would be away at work for 10 days and home for four days. One gets used to living these schedules, but the trade-offs between income and the health of the family unit are debatable. When considering a good job, both the health of the worker and the health of their family and community need to be taken into consideration, as the impacts of work spill over into the family and broader community.

‘Good jobs’ in Alberta’s oil industry are mostly for white men

The Canadian job market has changed significantly over the last half century. Typical “good jobs” in the decades following the Second World War were mostly held by male breadwinners and were full-time, year-round, benefit-providing, under a single employer, and expected to be held indefinitely. In the last three decades, with more women entering the workforce in an era of neoliberal reforms to government, these stereotypical good jobs have become less available. In their place, we see what researchers Cranford, Vosko, and Zukewich call the “feminization of employment norms,” characterized by increasing precarity, atypical work contracts, limited benefits, short job tenure, along with low wages, poor working conditions, and higher health risks.

By these standards, are oil industry jobs “good jobs?” Are they good for some, but not for others? When we consider “good jobs” should we also consider the impact they have on the collective good?

An Alberta government 2017 profile on the mining and oil and gas extraction industry finds that direct jobs in the oil industry accounts for six per cent of total employment in Alberta. Only a quarter of mining, oil and gas workers in Alberta are women, while three-quarters are men. In contrast, women make up 45.5 per cent of Alberta’s overall labour force. Additionally, about four in five mining and extraction workers are between 25 and 54 years of age (compared to 68 per cent of Alberta employees overall). These statistics paint a picture of an Alberta mining and extraction employee as a young/middle-aged man, but that’s only part of the story.

Sociologist Sara Dorow describes the frenzied work environment of Fort McMurray as a “pressure cooker.” Her research shows that it is women and visible minorities who bear many of the burdens of this pressure cooker. Through both their paid and unpaid work, these marginalized populations support and maximize men’s highly masculinized work in the oil industry, to the profit of those men, oil executives (who are mostly men), and shareholders of oil corporations (who, again, are mostly men).

While some women stay home with children to free up their partner’s time to work in the Alberta oil industry, other women and racialized workers are highly overrepresented in feminized and invisible service, retail, and care work in the oil sands region, while 90 per cent of those working as tradespeople and as transport and equipment operators are male (source: Statistics Canada). This gendered inequality of access to high-paying jobs means men’s incomes in the region are more than double that of women.

Nannies in the region—often Filipina Temporary Foreign Workers (TFWs)—pick up the care slack in homes where both parents work. This allows the parents to bring in more money and supports the further accumulation of profits by oil corporations. Outside of the home, other TFWs do much of the care and cleaning work that supports the retail, service, and hospitality sectors in the Fort McMurray region, including the mostly male tradespeople in oil industry work camps.

In 2016, there were 10,232 TFWs who came to Alberta, according to Employment and Social Development Canada data. Most worked in the service producing sector (6,484), and fewer worked in the good producing sector (3,748). The industry with the most TFWs (2,868) was accommodation and food services, showing that TFWs in Alberta tend to work in the service producing sector doing social reproductive work.

Although these care and cleaning jobs do provide employment, TFWs find themselves in particularly complex webs of precarity, with their limited access to citizenship rights and the labour market, as well as limited benefits, low wages, insecure jobs, and heightened health risks, all coupled with work permits tied to a specific employer. Labour researchers Foster and Barnetson point to the inherent racism in the creation of an inferior class made up of individuals often from the Global South of racial, ethnic, and linguistic minorities.

Social scientists O’Shaughnessy and Doğu find that Somali women working in Fort McMurray experience discrimination based on their gender, race, religion, and culture. With some employers reluctant to hire them, most end up working as cleaners. Some employers threaten to replace them with men. Those who wear long skirts and headscarves as a part of their religious and cultural practice are pressured to dress differently at work.

Even when women were able to access jobs directly in the oil industry, O’Shaughnessy and Doğu found that they were marginalized because of their gender, simultaneously for being too feminine and not feminine enough. Women who attempted to minimize their femininity physically (by wearing more masculine/neutral clothing and less makeup) or behaviourally (by acting less “bubbly” or friendly) were ostracized as “bitches” or as “mannish.” Women who maintained a more traditionally feminine appearance or personality were ostracized for being too “girly” or perceived as “not tough enough” to succeed in their job. In a field that already sees prejudice against hiring women, women being paid less than their male counterparts, and the normalization of verbal, physical, and sexual harassment, women face significant challenges and continued marginalization.

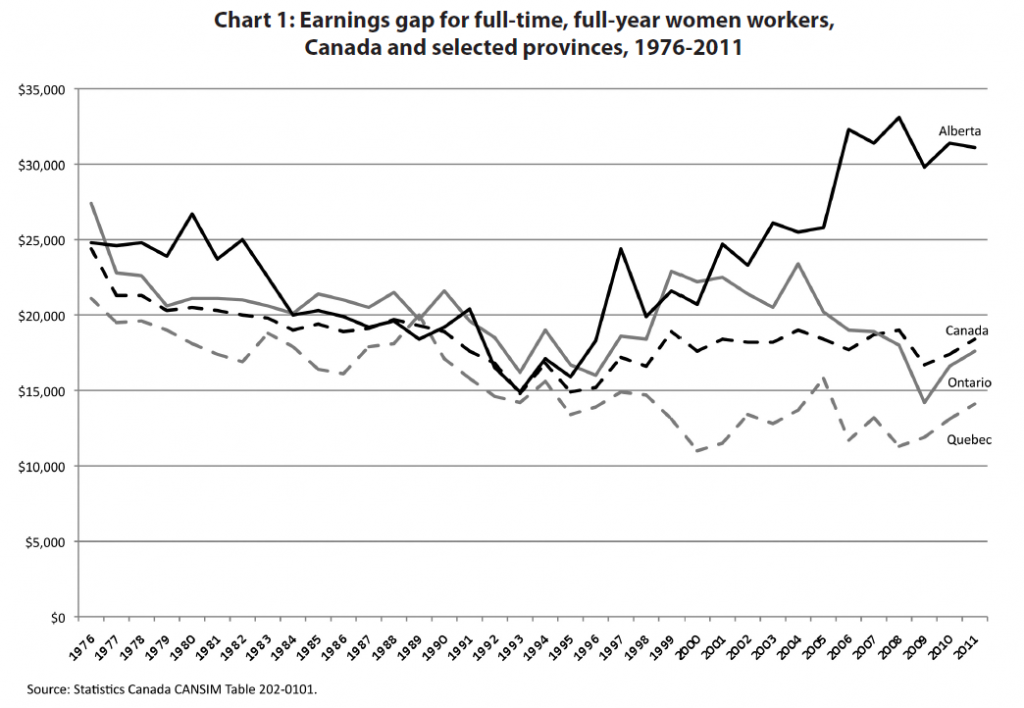

In a 2016 Parkland Institute report by law professor Kathleen Lahey, the sizable and persistent income gap between men and women is highlighted as the source of women’s economic inequality in the province. Although some level of gender income gap exists in all Canadian provinces and territories, and Canada has the third-largest gender income gap of wealthy (OECD) countries, Alberta’s gender income gap is the largest in Canada, with women working full-time, full-year, making an average of $31,000 less than their male counterparts.

Source: Lahey, 2016. Chart 1, p.5.

The gender pay gap is even more problematic when we consider that Alberta women are performing a “double day,” doing approximately 35 hours of unpaid house work per week, compared to men’s average of 17 hours.

In the resource industry specifically, Lahey confirms that higher-paying resource industry jobs are almost the sole domain of men, while women take up the lower-paying service and care jobs. Although service and care work undergirds the resource industry and is crucial for the whole economy, workers in these fields are valued less than workers labouring more directly in fossil fuel extractive processes.

The unequal worth of Indigenous workers

Gender, race, and country of origin are all built into the division of labour in the extractive industries. A recent Corporate Mapping Project blog highlights the complex relationship that Indigenous people have with the governments of Alberta and Canada. As a racialized minority, Indigenous people in Alberta also experience inequality and discrimination when it comes to the oil industry.

In a recent report on gender relations and Indigenous rights in energy development in northeast BC, Amnesty International found similar patterns of inequality and discrimination that researchers have identified as prevalent in Alberta’s oil industry. Among many things, the northeast BC study looked at the working conditions of Indigenous workers. First Nations and Métis workers noted, “their treatment varied enormously among companies and at different worksites.” Some felt “unwelcome and unsafe” at certain worksites, and said they’re the “last hired [and] first fired,” showing the underlying racism felt by some. As Chief Yahey explained, “There’s an old boys club that controls hiring … After everything is in play, they invite the First Nations in for the shovel jobs, the grunt jobs” (p. 40). This quote points to how Indigenous workers can be marginalized in the resource extraction workforce.

In addition, the Amnesty report highlights “the conflict between jobs that require long, multi-day and multi-week shifts often far from home, and cultural traditions of being out on the land with extended family” (p. 40). Indigenous peoples bear the brunt of the socio-economic and environmental burdens in regions where resource extraction happens on a huge scale, yet Indigenous peoples benefit the least from the massive profits generated by resource extraction.

The report captures this injustice succinctly:

Indigenous peoples whose lands and resources provide the basis for the wealth generated in the region, are excluded from a meaningful role in decision-making and bear a greater burden, including loss of culture and traditional livelihoods. The model of resource development, particularly the reliance on large numbers of transient workers, widens inequalities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and between women and men, negatively impacting Indigenous families access to food, housing, and social services and increases risks of violence (p. 50).

The Amnesty report also explores the working conditions of Indigenous women in resource extraction, and highlights the racism and sexism apparent in the industry. One woman who works in resource extraction summarized the masculine working environment, observing that women “work twice as hard to get half the recognition” (p. 40). The study described the work camps as, “a highly stressful environment. [The] physical isolation, and the drug and alcohol abuse at some camps all create an environment that can be unsafe for women” (p. 42).

One of the main findings of Amnesty’s report is that violence towards Indigenous women is intensified in resource extraction regions to the point where it is a routine part of life. Indigenous female participants in the study described the daily harassment they face on some worksites. One female worker said, “It’s a boys club, so if something happens you don’t say anything” (p. 42). Other women described sexual advances or expectations made by some of their male co-workers and, even worse, some women told stories of sexual assaults (p. 42).

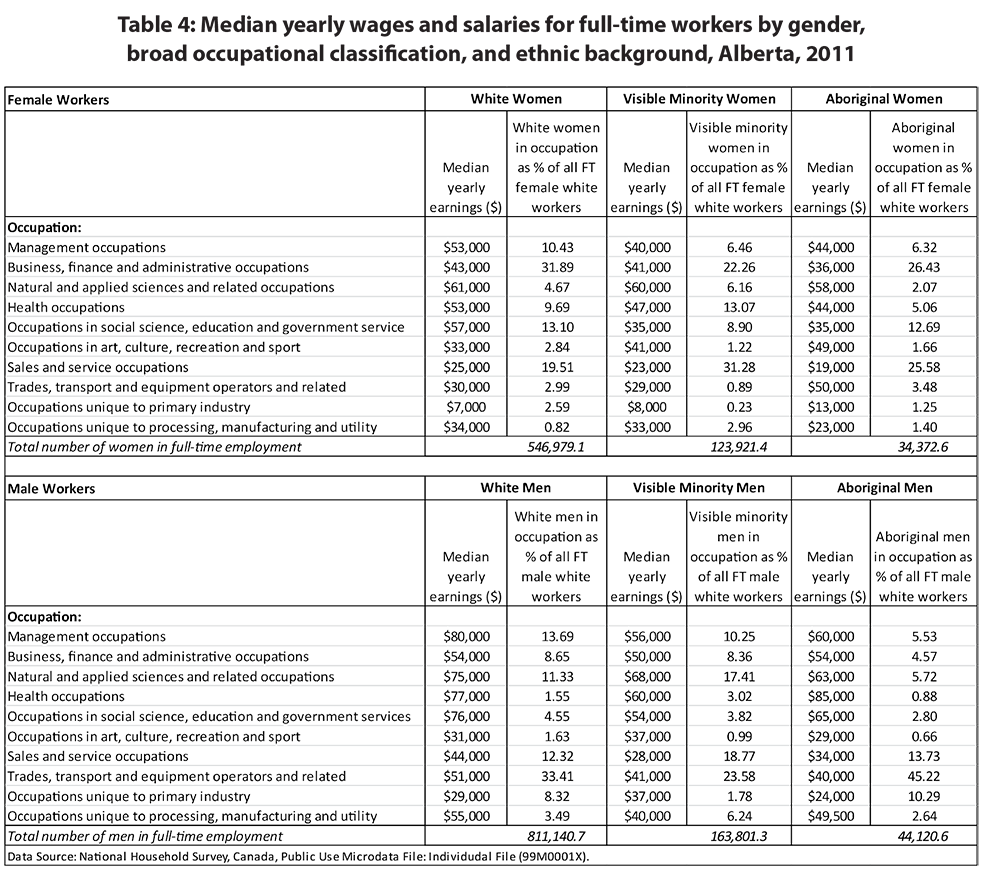

Returning to Alberta, the table below from Kathleen Lahey’s Parkland Institute report points to the different worth accorded to workers in various occupations based on their race and gender.

Source: Lahey, 2016. Table 4, p. 21.

The table shows that white men are significantly advantaged in employment in the province, with the highest incomes in nearly every field. Further, we see women over-represented in low-paying sales and service jobs, with visible minority and Indigenous women the most over-represented in these industries.

It is also clear from this table that Indigenous men and women tend to do better in certain public sector jobs, such as in healthcare, and arts, culture, and recreation and sport. Male and female Alberta workers of various races all seem to do a bit better in trades and transport jobs, showing the value in skilled trades work. However, white men still earn higher wages than most in this occupational category.

Overall, it is clear Alberta has a sharply segmented workforce based on differences in gender and race.

Conclusion

The recent throne speech sees the Alberta government claim its core responsibility to be to “make life better for everyday Albertans.” Although it is undeniable that the government has made policy changes that support that goal, one must ask: is life getting better for everyone or are some marginalized populations being left behind? How can the government and the private sector work together to ensure all Albertans prosper?

We have discussed the disconnect between the frontier mentality that exists in Alberta, the government’s and oil industry’s efforts to create “good jobs,” and the limited access women and racialized workers, including Indigenous people, have to “good jobs” in the oil patch and region. Some individuals from these marginalized groups are able to access high-paying oil industry jobs, but they are the exceptions and not the rule in the discriminatory division of labour that undergirds Alberta’s oil industry specifically and Alberta’s overall labour force generally.

Pay equity legislation is one way the government of Alberta can begin to deal with the issues discussed here. Alberta is far behind other provinces in the area of pay equity. Though the public sector has some checks and balances in place to ensure more equal opportunities for marginalized populations to gain access to “good jobs” and decent remuneration, the absence of pay equity legislation permits parts of the private sector to function in ways that maintain marginalization.

The government of Alberta’s inaction on pay equity to date ensures its ongoing complicity in the maintenance of economic inequality, where private sector employers and white male workers benefit from the continued marginalization and super-exploitation of gendered and racialized workers.

A story recently emerged from the oil patch in which a young, black, Muslim woman named Amino Rashid is filing a human rights complaint against her employer for discrimination, due to alleged Islamophobic comments directed at her while working.

The allegations are regarding an incident that involved other workers targeting her for wearing a hijab. In one of the alleged incidents, she was told to take off her hijab because it was supposedly making others “uncomfortable,” and a co-worker allegedly said, “this is how things are done around here.” In a CBC interview she noted, “That’s how it is as a black girl in this world. You must go through those obstacles in life,” but she is filing the complaint to fight for herself and others. Showing her bravery and resilience, she stated, “I want all the people who can’t speak for themselves, that feel like they don’t have a right to speak up, I want them to know that I’m speaking up for you.” This story highlights the blatant discrimination and negative experiences faced by minorities in the workplace, in the Wild West of Alberta, where frontier masculinity is the expected norm, and minorities are “othered” for their differences in race, religion, and gender.

As Albertans, we should be disappointed to hear that “this is how things are done around here.” From the research it is clear that our workforce is segmented by race and gender, in which women and ethnic minorities earn less money and experience more precarious work. But does this mean discrimination has been normalized? One of the positive outcomes of this story is that Husky Energy is taking these allegations seriously and is launching an investigation of its own into the contractor that employed Rashid. It is important that workers, employers and unions take these types of discrimination allegations seriously, and act on them accordingly. But the response shouldn’t end there. As Albertans, we need to take the evidence of a racialized and gendered workforce seriously, and change how things are done around here.

This post is part of the Corporate Mapping Project, a research and public engagement initiative investigating the power of the fossil fuel industry in Western Canada. The CMP is jointly led by the University of Victoria, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, and Parkland Institute. This research was supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Author: Angele Alook, Nicole Hill & Ian Hussey

Dr. Angele Alook is a proud member of Bigstone Cree Nation and a speaker of the Cree language. She recently successfully defended her PhD in sociology from York University. Her dissertation is entitled “Indigenous Life Courses: Racialized Gendered Life Scripts and Cultural Identities of Resistance and Resilience.” She specializes in Indigenous feminism, life course approach, Indigenous research methodologies, cultural identity, and sociology of family and work. Angele currently works in the labour movement as a full-time researcher for the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees. She is also a co-investigator on the SSHRC-funded Corporate Mapping Project, where she is carrying out research with Parkland Institute on Indigenous experiences in Alberta’s oil industry and its gendered impact on working families.

Ian Hussey is a research manager at Parkland Institute. He is also a steering committee member and the Alberta research manager for the SSHRCC-funded Corporate Mapping Project.

Nicole Hill is a PhD student in the sociology department at the University of Alberta and she was a research assistant from 2016 to 2018 at Parkland Institute. She is a graduate of Athabasca University’s Masters of Arts in Integrated Studies program, where she focused on equity studies. Nicole’s current research is on maternity care experiences.