One year ago this week, the government of Alberta announced its Climate Leadership Plan, and in June 2016, the enabling legislation for the plan, Bill 20, the Climate Leadership Implementation Act, received royal assent.

Alberta’s Climate Leadership Plan is based on the report developed by the government’s Climate Change Advisory Panel, chaired by economist Andrew Leach, an associate professor at the University of Alberta’s School of Business. Following an extensive consultation process, the advisory panel made recommendations in four key areas.

One specific recommendation was the introduction of a carbon levy—commonly referred to as a carbon tax—on transportation and heating fuels that emit greenhouse gases (GHGs) when combusted, such as gasoline, diesel, natural gas, and propane.

A growing number of economists and businesspeople are in favour of putting a price on carbon because it is a market-based approach known to reduce emissions at a low economic cost. As the government’s Climate Leadership Discussion Document explains, “A price on carbon provides a financial incentive for emitters to reduce their emissions. This can spur the adoption of technology, efficiency and conservation, and provides emitters with flexibility to reduce emissions in a way that best suits their individual processes, abilities and circumstances.”

A considerable amount of ink has been spilled in the last year about the Climate Leadership Plan, with much of the public discussion and political jockeying focused on the new carbon levy that will take effect on January 1, 2017. With just over a month until it goes into effect, here are 10 key facts about carbon pricing in Alberta.

1. Alberta has had a price on carbon for large industrial emitters since 2007

Alberta’s Specified Gas Emitters Regulation (SGER) first came into effect in 2007 under the former Progressive Conservative government. The SGER applies to industrial facilities that emit 100,000 tonnes or more of GHG emissions per year.

The original PC legislation required these facilities to reduce their site-specific emissions intensity by 15% annually. The NDP increased the reduction target to 20% per year effective January 1, 2017.

Businesses have four ways to comply with the SGER:

- make improvements to facilities to reduce emissions,

- use emission performance credits generated at facilities that achieve larger than required reductions,

- buy Alberta-based carbon offset credits, and

- contribute to Alberta’s Climate Change and Emissions Management Fund.

Facilities that do not achieve the required emissions reductions can pay $20 for every tonne over their reduction target to the fund. The price per tonne increases to $30 as of January 1, 2017.

Alberta’s 2016 Fiscal Plan says the SGER will be phased out at the end of 2017, “when the province will transition to product and sector-based performance standards. Further details on performance standards will be made public after industry consultations” (page 93).

2. Alberta’s new carbon levy will apply to transportation and heating fuels on January 1, 2017

Alberta’s Budget 2016 presented the provincial government’s two-part plan to price carbon, which includes the above changes to the SGER and the introduction of a new carbon levy on transportation and heating fuels. The levy will not apply directly to consumer purchases of electricity.

Combined, the SGER and the carbon levy will apply to 78-90% of Alberta’s GHG emissions. The two mechanisms are designed to work together so Albertans are not charged twice on the same emissions.

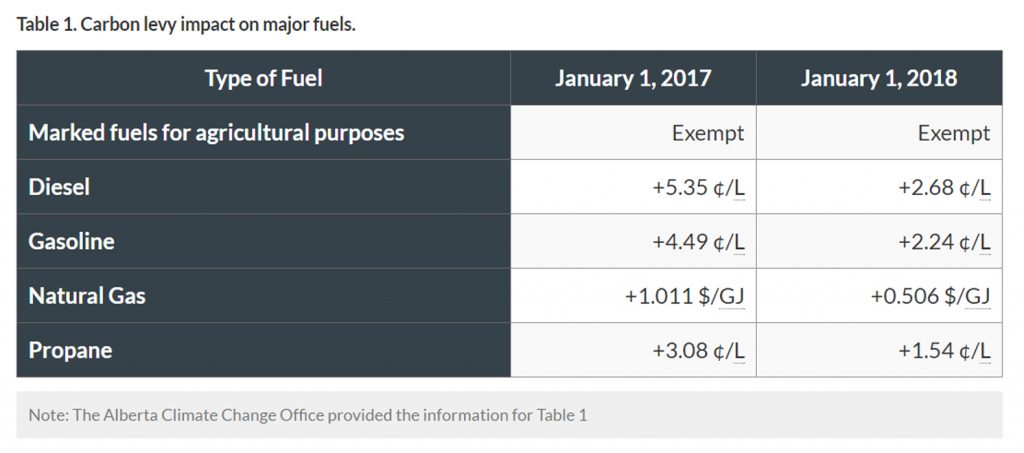

Alberta will still have the third lowest total provincial taxes/levies on gas and diesel in 2017, after Saskatchewan and Manitoba (Alberta 2016 Fiscal Plan, page 96). The major fuel rates of the Alberta carbon levy are as follows:

The Climate Change Advisory Panel recommended that the carbon price should increase over time, but the provincial government stated in the 2016 Fiscal Plan that it “will not increase the carbon price further until the economy is on a stronger footing and once the actions of other jurisdictions, including those of the federal government, are better known” (page 94).

3. British Columbia introduced a revenue-neutral carbon tax in 2008

BC’s carbon tax is now $30 per tonne, which adds 6.67 cents to the price of gas at the pumps. The result has been that per capita fuel use covered by the BC tax fell 16% from 2008 levels by 2014.

BC’s carbon tax is revenue neutral, meaning that public revenue generated by the carbon tax must be offset by reductions in other provincial taxes.

4. Alberta’s carbon levy is not revenue neutral, and that’s a good thing

In BC, about two-thirds of carbon tax revenues have been used to cut corporate income taxes, which economist Marc Lee says is bad fiscal policy because it makes it harder for the BC government to invest in public infrastructure and services.

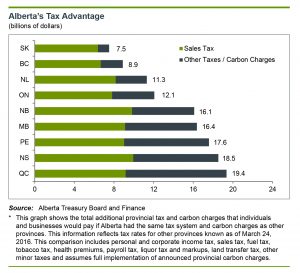

The stated position of Alberta’s Wildrose Party is that it would scrap the new Alberta carbon levy and consider replacing it with a revenue-neutral carbon tax similar to BC’s. This seems like an odd choice given that Alberta already has a sizeable revenue disadvantage compared to other provinces, as is depicted in the following chart from Alberta Treasury Board and Finance. Alberta remains the only province without a provincial sales tax.

The Wildrose has failed to date to produce a shadow budget, so it is hard to say exactly what cuts would be made to offset a revenue-neutral carbon tax if the party were in power and introduced such a tax. However, in April Wildrose leader Brian Jean said his party would balance the budget by 2019, but would not raise taxes or borrow money to do so. This would likely mean cutting 6-8% of expenditures this year and in each of the next three years, and the complete abandonment of infrastructure spending, especially on bigger-ticket items like the Calgary cancer centre.

5. Instead of being revenue neutral, Alberta’s carbon levy revenue will be invested back into the provincial economy

Expected to raise $9.6 billion over the next five years, the government of Alberta will use about 65% of the carbon levy revenue to “pay for the transition to a more diversified economy” as follows:

- $3.4 billion for renewable energy, bioenergy and technology

- $2.2 billion for green infrastructure, such as improved public transit

- $645 million for Energy Efficiency Alberta, a new provincial agency that will help families and businesses become more energy efficient

Some specific carbon levy investments were announced this fall, including the installation of solar panels at 36 school projects and support for energy-intensive farm operators to reduce their emissions, and thus their energy costs, through efficiency upgrades.

6. Most Alberta families will receive rebate cheques larger than their increased costs

The remaining $3.4 billion in carbon levy revenue generated over the next five years is earmarked to help Albertans adjust to the impacts of the Climate Leadership Plan:

- $2.3 billion in rebates for low- and middle-income families

- $865 million to cover the cut in the small business tax rate from 3% to 2%

- $195 million to support coal communities, Indigenous communities and others with adjustment

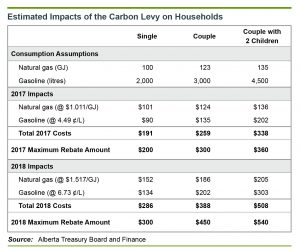

The cost of the carbon levy per household will vary, depending on energy use and driving patterns. About 60% of Alberta households will receive rebate cheques that cover the increase to their monthly costs.

The following table from Alberta’s 2016 Fiscal Plan (page 96) shows the typical direct impact Albertans will face:

As Andrew Leach explains, “the potential regressive nature of emissions reduction policies is why first BC and now Alberta have opted for rebates to shield lower-income consumers from the reduced purchasing power which would otherwise disproportionately affect them under a carbon price.”

7. The carbon levy will not drive investment out of Alberta

At the Wildrose Party’s annual general meeting on October 29th, party leader Brian Jean said, “Once you dissuade investors from coming into Alberta, once you have energy companies leave Alberta … it’s very difficult to get them back.”

By contrast, Leach argues the carbon levy alone won’t make Alberta uncompetitive, explaining in an interview with the Calgary Herald that “people aren’t going to invest or not invest based on the carbon price. They’re going to invest or not invest based on the overall return of the facility, so that’s where the government should be acting.” Leach recommends the government “[makes sure] that the broader fiscal, labour, economic environment is conducive to building [new projects], make sure that we have access to markets … but I would put at the bottom of the list free carbon emissions.”

Regarding the broader fiscal, labour, and economic environment in Alberta, higher labour costs in Alberta make construction projects more expensive than those on the US Gulf Coast, but our royalty and corporate income tax rates are low and not likely to dissuade investment in the oil industry. Alberta’s corporate income tax rate is 12%. As of January 1, 2016, Saskatchewan and Manitoba have the same rate, while BC’s rate is 11% and Ontario’s is 11.5%.

As investigative journalist Andrew Nikiforuk wrote recently, “Consider these revelations from a few quarterly corporate reports. Cenovus, for example, paid only $3 million in royalties on bitumen sales worth $1.1 billion in the first six months of 2016. That’s less than a one per cent royalty. CNRL paid $6 million on sales of $1.9 billion worth of bitumen. Suncor paid $48 million in royalties on $4.7 billion worth of gross bitumen sales. And on it goes.” It is hard to look at those numbers and conclude that Alberta is charging “too much” for royalties.

Beyond the oil industry, the Government of Alberta is incentivizing investment in electricity generation from renewable sources (wind, hydro, and solar), with a target of having 30% of Alberta’s electricity provided by renewable sources by 2030. This target provides clarity for these industries and for potential investors. The government estimates clean energy projects will bring $10.5 billion and 7,200 jobs to the province in the next 15 years.

8. Large corporations are in favour of putting a price on carbon

When Alberta’s Climate Leadership Plan was announced last November, four of Canada’s largest oil sands producers issued a statement in favour of the plan, including the carbon pricing regime. In their own words, “Canadian Natural Resources Limited, Cenovus Energy Inc., Shell Canada Limited and Suncor Energy Inc., support the Government of Alberta’s climate plan related to the oil and natural gas industry, which includes a carbon pricing regime coupled with an overall emissions limit for the oil sands. … By directing revenue generated from the new carbon pricing regime towards the development of potentially game-changing greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction technologies, this made-in-Alberta plan lays the foundation for the province to become a global leader in addressing the climate change challenge.”

A joint statement in favour of carbon pricing was released in July by federal Minister of Environment and Climate Change Catherine McKenna, and a list of large corporations operating in Canada, including several oil companies and big banks.

The Government of Canada also signed an international joint statement supporting carbon pricing along with numerous nations and corporations including Nestle, Unilever, Michelin, Statoil, BG Group, and HSBC.

Finally, here’s a list of more than 1,000 corporations, including over 300 institutional investors, who support carbon pricing.

These joint statements indicate there is a growing understanding in Alberta, Canada, and global business communities that not taking action on climate change is costly.

As economist Andrew Leach wrote, “not reducing emissions in Alberta is also potentially very costly. We’ve already seen policies and actions aimed at our resource sector whether through the rejection of pipelines, the application of low carbon fuel standards, or challenges to companies investing here from their shareholders or from sustainable investors. If Alberta chooses not to act, those costs won’t go away.”

9. Since the publication of Alberta’s Climate Leadership Plan, the federal government has announced a national carbon-pricing plan

In October 2016, the federal Liberals announced a national carbon-pricing plan that would require all provinces and territories to have some kind of carbon price, either a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system, by 2018.

Premier Notley said her government supports the federal initiative “in principle,” but also that “Alberta will not be supporting this proposal absent serious concurrent progress on energy infrastructure.” This pro-pipeline stance by the premier works against her government’s stated ambition to be a leader in fighting climate change.

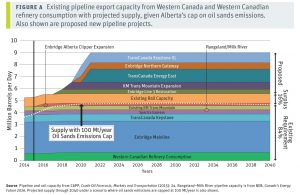

Besides the alarming fact that the world is on track for 3C of warming under current global climate commitments, Canada already has enough pipeline and rail capacity to transport the oil sands equivalent of Alberta’s 100 megaton emission cap, as the following chart produced for a recent Parkland Institute/Canadian Centre for Policy alternatives report by renowned earth scientist David Hughes shows:

Premier Notley’s pro-pipeline stance is an example of the new climate denialism: “In the new form of denialism, the fossil fuel industry and our political leaders assure us that they understand and accept the scientific warnings about climate change – but they are in denial about what this scientific reality means for policy and/or continue to block progress in less visible ways.”

If Alberta is to become a real global leader in the fight against climate change, then the provincial government needs to stop advocating for new pipelines. To fulfill the global Paris Agreement on climate change we need to start reducing emissions immediately, and that means we can’t build new pipelines intended to last for several decades.

10. The social cost of carbon is much higher than what is accounted for by the governments of Alberta and Canada

The social cost of carbon (SCC) is a measurement for estimating the economic damages from emitting a tonne of carbon. Examples of the social costs that arise from carbon pollution include negative health effects, decreased food production, coastal damage, and the increased frequency of extreme weather events like floods and wildfires.

In 2009, economist Mark Jaccard and associates estimated that to help ensure global temperatures stay below 2C warming above pre-industrial levels, the price on carbon in 2010 should be $50/tonne, increasing to $200/tonne by 2020, far above the current frameworks of the governments of Alberta and Canada.

The 2C target isn’t even considered by scientists to be enough to ensure a safe climate anymore. The global Paris Agreement on climate change aspires for a 1.5C target, which scientists say will enable us to avoid some of the worst effects of runaway global warming.

Our governments need to come to grips with this reality. The current climate change plans at both the provincial and federal level are insufficient if we are to do our part in mitigating the worst effects of climate change, especially given our provincial and national dependence on extractive carbon-heavy industry and the high consumption patterns of Canadians. A steadily increasing carbon levy is just the beginning of what must be a suite of urgent government responses to the climate crisis.

—

This blog was originally published by Parkland Institute.

Author: Ian Hussey

Ian Hussey is a research manager at Parkland Institute. He is also a steering committee member and the Alberta research manager for the SSHRCC-funded Corporate Mapping Project. Before joining Parkland Institute, Ian worked for several international development organizations, including as the co-founder and executive director of the Canadian Fair Trade Network. Ian holds BA Honours degrees in Sociology and in English from Acadia University, an MA in Sociology from the University of Victoria, and his PhD courses and exams at York University focused on the sociology of colonialism and on political economy. His writing has appeared in the Globe and Mail, New Political Economy, Edmonton Journal, National Observer, and The Tyee.