In Western Canada’s slow lurch towards sane climate and energy policy, two prominent arguments have been advanced for the continuation of business-as-usual for the fossil fuel industry in BC and Alberta. Both are interesting because they invoke the need for climate action to justify the further growth of fossil fuel production.

The first argument comes in support of Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion (TMX). It goes like this: Alberta’s buy-in to climate action is dependent on new pipelines being built, and undoing that compromise would unravel the fragile Pan-Canadian Framework (the federal-provincial climate agreement made in November 2016). A variant of that argument is that as long as good climate policies (like a carbon tax) are in place, then we need not worry about pipeline expansion.

The second argument (found here and here, for example) focuses on BC’s fossil fuel of choice: liquefied natural gas (LNG). That argument is that a massive expansion of the province’s gas industry through LNG exports would actually be good for global climate action efforts, because they would reduce coal usage in other countries.

In both cases we see wishful thinking based on the preposterous assumption that expanding energy-intensive unconventional fossil fuel production (bitumen mining and gas fracking) in Western Canada is tantamount to good climate policy.

Let’s start with TMX, the need for which is justified by ever-expanding oil sands production in Alberta. That province’s climate plan includes a cap on oil sands emissions—but one that allows emissions to grow a whopping 40% above current levels. The Alberta plan also has some bona fide climate actions (which I describe in this post), including a (well-designed) carbon tax and a commitment to reduce leaks of methane—although mostly, the plan is predicated on a welcome phase-out of coal-fired electricity.

In pledging to eliminate coal-fired electricity, Alberta is coming late to the party. Ontario has already phased out its coal electricity, and Maritime provinces have mostly done the same. Phase-outs in these provinces led to emission reductions that have roughly offset Alberta’s increased oil sands emissions, meaning Canada as a whole has stayed about flat in terms of overall national emissions.

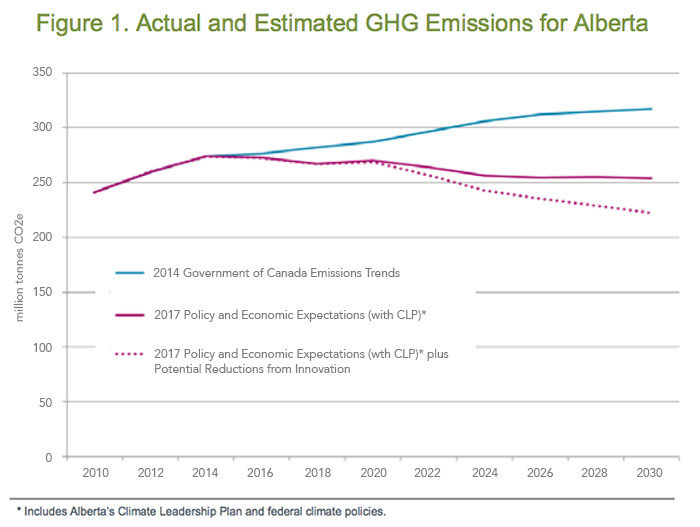

This is an eerie parallel to what Alberta is proposing for itself. By 2030, emission reductions from phasing out coal, among other measures, merely facilitate increased emissions from oil sands expansion. Here’s what that looks like, according the Alberta government’s own estimates:

So Alberta is patting itself on the back for a plan to keep emissions essentially flat (pink line) when they need to be coming way down. The dotted pink line implies greater potential but this is largely hand-waving based on “innovation.” The province could start to bend the curve by merely keeping oil sands emissions at 2015 levels, but that is not on the table.

Thus, the only way Alberta’s emissions would go down is if other countries do not buy Alberta fossil fuels. But the industry and government want to bring to market all the supply they can justify economically.

Furthermore, this math conveniently does not count the much greater carbon emissions downstream when fossil fuels extracted in Alberta are combusted in other countries. The total amount of extracted carbon (that would go into the atmosphere) from Alberta soil alone, facilitated by Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion, is 84 million tonnes of CO2 per year. This is about the same amount of emissions as all of the cars currently driving on Canada’s roads.

I’ve so far picked on Alberta, but don’t think I’m giving BC a free pass. Yes, the new BC government rightly objects to a pipeline that threatens disastrous spills on land and from tankers passing through the Burrard Inlet. But it is also encouraging growth of its own fossil fuel extraction—namely the natural gas sector through proposed LNG exports—and government officials just recently went on a mission to Asia to promote it.

The argument that LNG will displace Asian coal, and thus be a net gain for global climate efforts, is one of those zombie ideas that never seems to die. There is a small kernel of truth in it—which is that at the point of combustion, gas is about half as emissions-intensive as coal in producing the same amount of energy.

However, getting liquefied gas to Asia is a very energy-intensive endeavour. First, it requires huge amounts of energy and emissions to frack, process and pipe gas to the coast, and even more energy is required to liquify it for trans-ocean shipment by tanker. This greatly reduces the emissions advantage relative to coal.

The advantage is lost entirely when we consider leakages that can occur throughout the supply chain and in particular during the fracking process, in which a high-pressure injection of water, sand and toxic chemicals a couple of kilometres below the earth’s surface cracks open shale rock to release gas. When leaked into the atmosphere, natural gas—which is methane—dissipates relatively quickly but is a super-potent greenhouse gas—100 times more warming than carbon dioxide. Recent research shows that these leakages are much larger than industry has been reporting.

Finally, whether LNG would actually displace coal in other countries is an open question. China has a growing appetite for energy of all types. It is possible that LNG exports to China would displace coal, but it is also possible they would displace renewables. In the case of exports to Japan or Korea (the world’s largest LNG importers), they would almost certainly displace renewables or nuclear power.

To date no one has proposed a trade agreement that would guarantee that LNG replaces coal. We do not control what happens outside our borders—but we do control what we dig up and sell on world markets.

Alas, many seem to have bought into these convenient arguments that we can have it every which way we choose. They ignore the central fact that commitments to the Paris Agreement are far from sufficient to keep global temperature increases below 2ºC, and that the Pan-Canadian Framework itself is insufficient to meet Canada’s inadequate Paris pledge.

If Canada wants to get serious about climate action, that means winding down fossil fuel industries. That does not need to happen overnight, but over two to three decades. And it can be done in a way that stabilizes employment and mitigates larger problems for workers whose livelihoods are tied to boom-and-bust commodity price cycles. But certainly we cannot keep growing the industry. To pretend otherwise is simply a delusion.

While Albertans may feel that their province is being singled out for disproportionate measures because it cannot grow its already oversized fossil fuel industry in a carbon-constrained world, BC will also need to put a pin in its LNG fantasy. Time for talk is over: we need real action that invests and creates jobs in green alternatives.

—

This post is published as part of the Corporate Mapping Project, a research and public engagement initiative investigating the power of the fossil fuel industry. This research is supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Author: Marc Lee

Marc Lee is a Senior Economist at the CCPA’s BC Office and a co-investigator with the Corporate Mapping Project (CMP).

In addition to tracking federal and provincial budgets and economic trends, Marc has published on a range of topics from poverty and inequality to globalization and international trade to public services and regulation. Marc is Co-Director of the Climate Justice Project, a research partnership with UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning that examines the links between climate change policies and social justice.